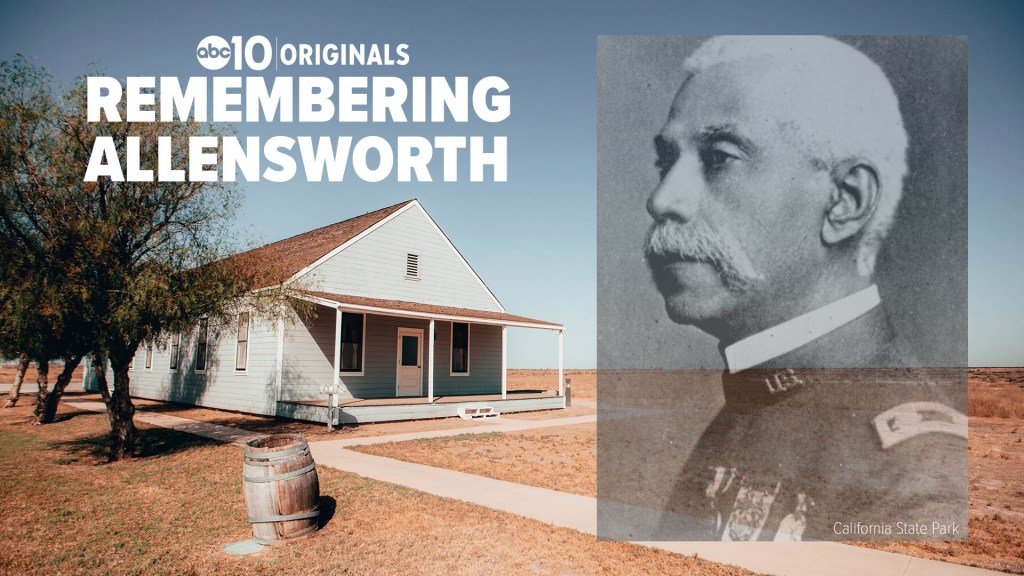

Allensworth, the first town in California established exclusively by African Americans, was founded in 1908 by a group of men led by Colonel Allen Allensworth. Born a slave in Louisville, Kentucky in 1842, Allensworth became the highest ranking black officer in the U.S. Army when he retired in 1906.

As a boy, Allensworth was punished for learning to read and write which was unlawful for enslaved people in Kentucky and across the South. During the Civil War, he escaped and sought refuge behind

the Union line, where he worked as a civilian nurse in the Army Hospital Corps.

From 1863 to 1865, Allensworth served in the U.S. Navy and afterwards became an ordained Baptist minister. In 1871, Allensworth met Josephine Leavell, a school teacher, organist and pianist. They were married on September 20, 1877. Josephine Allensworth worked diligently with her husband to promote his educational and religious works. The couple had two daughters, Nellie and Eva.

In 1882, Allensworth discovered that of the four black Army regiments (the Buffalo Soldiers), there were no black chaplains. He immediately sought that appointment. On April 1, 1886, President Grover Cleveland appointed Rev. Allensworth as chaplain of the 24th Infantry at the rank of Captain, with the responsibility for the spiritual health and educational well-being of black soldiers in the regiment.

At the time of his appointment he was only the second African American, after Henry Plummer, named to serve as a U.S. Army Chaplain. Allensworth retired as a lieutenant-colonel on April 7, 1906, having achieved the highest rank of an African American in the U.S. Armed Forces.

After his retirement, Allensworth traveled widely throughout the United States lecturing on the need for self-help programs which would enable African Americans to become more self-sufficient. In 1904, the Allensworth family decided to settle in Los Angeles. One of Allensworth’ s goals was to identify a town-site in the state of California where African Americans might start a new life together outside the restrictions of the Jim Crow South.

In 1906, Allensworth met Professor William Payne who was born in West Virginia in 1885, but was raised in Ohio where his father worked in the coal mines. After completing high school, Payne attended Dennison University In Granville, Ohio, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in 1902. Just before his graduation he met and married Zenobia B. Jones, who also attended Dennison University.

Payne served as Assistant Principal at Rendville School in Rendville, Ohio for seven years and later as a Professor at the West Virginia Colored Institute for two years. In 1906, Professor Payne and his wife moved to Pasadena, California where he hoped to be a “teacher of teacher.” Payne was not eligible to teach in Los Angeles because he lacked prior teaching experience in California.

While in southern California, however, Payne met retired colonel Allensworth and the two men decided to pool their talents to create what was then termed a “Race Colony” for the improvement of African Americans across the nation.

Joining Allensworth and Payne to establish their race colony were three other men, Dr. William H. Peck, an AME minister in Los Angeles, J.W. Palmer, a Nevada miner; and Harry Mitchell, a Los Angeles Realtor. Allensworth selected a location in southwest Tulare County which had virgin soil and plentiful water.

Together they created the California Colonization and Home Promoting Association and soon thereafter filed a township site legal plan on August 3, 1908 to form the town of Solito, which had a depot connection Los Angeles and San Francisco on the Santa Fe Railroad. The town’s name was changed that same year to Allensworth, to honor its most prominent founder.

Town founders established the Allensworth Progressive Association as the official form of government to conduct its affairs. Townspeople elected officers and held town meetings to encourage the civic participation of all of its residents. In 1912 Allensworth became a voting precinct and had its own school district encompassing thirty-three square miles. At its peak in the early 1920s, Allensworth had as many as 300 residents.

Once the school district was established in in 1912, the Allensworth School, costing $5,000, was built with funds donated by local citizens. It was the largest capital investment made by the community, epitomizing the importance of education for the town. The one-room schoolhouse included elementary, intermediate, and high school students. The school was governed by an elected body of three board members. The original trustees were Josephine Allensworth (who also served as the first teacher), Oscar Overr and William H. Hall.

Allensworth School also served as the town center for events and meetings. The Allensworth Progressive Association, the Women’s Improvement League, the Debating Society, the Theatre Club, and the Glee Club all met in the building. The most memorable of the year, however, was commencement which took place in June at the end of each school year.

Allensworth was sanctioned a judicial district by the State of California in 1914, and soon afterwards Oscar Overr and William H. Dotson became the first African Americans to hold elected offices as Justice of the Peace and Constable, respectively. A branch of the Tulare County Library and a post office were established with Mary Jane Bickers serving as the first postmistress. On July 4, 1913, an official reading room was established in a separate library building.

Agriculture dominated the economy of Allensworth as several farmers moved in or near the township. The town also had several businesses including a barber shop, bakery, livery stable, drug store, machine shop, and the Allensworth Hotel.

In keeping with Colonel Allensworth’ s idea of self-help and self-reliance programs, city leaders in 1914 proposed to establish a vocational education school based on the Tuskegee Institute model and the ideas of its founder, Booker T. Washington. Although it received support for a state funding appropriation from Fresno and Tulare County representatives in the California State Senate and Assembly, the proposal was defeated by the entire state legislature.

The town suffered a far greater loss later in 1914 when Colonel Allensworth died after being struck by a motorcycle while visiting Los Angeles. The town however continued to grow due to the leadership of Oscar Overr, the Justice of the Peace, and Professor William A. Payne, the school principal. New residents continued to arrive and the town continued to prosper until the early 1920s.

Allensworth’ s prosperity peaked in 1925 and after that date the lack of irrigation water begin to plague the town. Irrigation water was never delivered in sufficient supply as promised by the Pacific Farming Company, the land development firm that handled the original purchase. As a result, town leaders were engrossed in lengthy and expensive legal battles with Company, expending scarce financial resources on a battle they would not win.

By 1930 the town’s population according to the U.S. Census, had dropped below 300 people, as residents and nearby farmers began to leave in search of other employment. The deficient water supply would not sustain the agricultural and ranching enterprises at that time. The residents who remained behind attempted to keep the community alive by designing new methods of farming, creating other businesses, and drilling new water wells.

Yet through the early 1960s, the town continued to exist even if it did not thrive. Then in 1966 the State of California discovered high levels of arsenic in the drinking water. Most residents left but 34 families remained, leaving Allensworth all but a ghost town. The water was contaminated on purpose if you ask me. SG64

When drinking water gets contaminated, there’s usually a polluter to blame. Most likely it’s the fault of big industry spewing out toxic fertilizers or synthetic chemicals.

But in nearly 100 communities in California, this isn’t the case. They have water that is contaminated with a naturally occurring chemical: Arsenic.

Allensworth, California is one of those communities.

It’s a tiny town a couple of hours north of LA in California’s Central Valley. It’s in Tulare County, one of the poorest counties in the state. And it was the very first all-black community in California, founded in the early 1900s.

Today, it’s home t

o about 500 people — but they don’t have water that’s safe to drink.

Denise Kadara lives in a town where she can’t drink the water. If she does, she faces a litany of health risks — the most serious being cancer.

“It’s not comforting,” she says. “I mean, it’s just like being in Flint and having lead in your water.”

Denise lives in the tiny

community of Allensworth, California, and there’s been arsenic in her drinking water on and off for decades. The problem stems back to the early 1900s when Allensworth was founded as the state’s first all-black community.

Located about two hours north of Los Angeles, the tiny town is home to about 500 residents. It’s in Tulare County — one of the poorest in the state — and it’s considered severely disadvantaged.

Allensworth fits the description of the majority of roughly 100 other communities in California that have arsenic in their water, too. Most of these towns are clustered in the San Joaquin Valley and are predominantly poor and/or Latino or African American.

Arsenic is a naturally occurring chemical, and it’s a carcinogen. It can cause bladder, lung, kidney, and skin cancers, along with a whole slew of other health effects, including diabetes, neurological problems, a

nd developmental disorders.

“My first concern was our children were drinking that water,” said Denise. “What effects did it have on them?”

The toxin has particularly alarming effects on the development of children’s brains. In one stud

y out of Maine, children who were found drinking arsenic below the legal limit of ten parts per billion tested five to six points lower on an IQ test.

Denise told me that she’s heard stories from her other sister, Regina, about members of the community getting sick.

Regina has lived in Allensworth for over 30 years. She says she knows half a dozen families who have seen many of their family members die of cancer. She says most of the cases have been either stomach, prostate, or liver cancer.

Both prostate and liver cancer are connected to arsenic poisoning. But there’s no way to really know if it’s related to the arsenic in the water.

It’s also hard to know how many residents are aware that the water isn’t always safe to drink.

Every time there is too much arsenic in Allensworth’s drinking water, residents are supposed to get a notice in the mail from the Allensworth Water District — it’s required by law. But the notice downplays the health risks. It suggests the water is still safe to drink — that another water supply isn’t necessary.

Denise and her two siblings, Denis Hutson and Sherri Hunter, first learned about arsenic in the water from their mother, Nettie Morrison. And Nettie learned about it in the early 1980s.

At that point, there was more than 10 times the legal limit set today.

“My mother started going to the county,” says Sherri. “She asked question after question after question, and people started realizing, ‘This lady is not going away,’ and, ‘She is not joking,’ and, ‘We can’t just pacify her to shut her up because she will be back tomorrow.’”

Nettie’s efforts paid off and helped Allensworth get two new wells. One was drilled in the 1980s and the other in the 1990s.

Those two wells had

water that was safe to drink, according to the standards set by the EPA.

But in 2008, the EPA changed its standards. It lowered the legal limit of arsenic from 50 parts per billion to 10 parts per billion.

Ten parts per billion isn’t necessarily safe. It’s just the amount the EPA decided was practical. The agency weighed the health risks of the toxin against how much it would cost to upgrade water systems throughout the country. It even considered lowering it to just 3 parts per billion, but that would have cost too much.

Really, any amount of arsenic in your water isn’t good for you.

The standards the EPA set at 10 parts per billion were adopted by California, and Allensworth’s water went out of compliance again.

A few years later, Denise, Denis, and Sherri started to get involved because their mom, Nettie was getting older. They have been working for over a decade to find another water source.

Tulare Lake doesn’t exist today. It’s all dried up, and it’s filled with acres of pistachio and almond trees. Before it was drained by heavy agriculture use, it was the biggest lake west of the Mississippi.

“It was just absolutely beautiful,” he says. “And the railroad track was there, so Allensworth became this hub. The farmers, they had to pay black people and this town was prospering.”

But their success didn’t last very long. Four catastrophes, one after another, destroyed the town.

First, the town’s wells dried up since farmers moving to the area were diverting streams and rivers from entering Tulare Lake.

Most communities would just drill a deeper well, but the company that sold Colonel Allensworth the land didn’t follow through on its promise to provide the town with a water system. It refused to help drill another well and left them with thousands of dollars of debt.

Then, about a year later, wealthy farmers nearby Allensworth raised money to build a railroad stop in Alpaugh, the mostly-white town next door. The new station took away most of the business from Allensworth’s station, which was used by farmers to ship their crops and livestock to market. By 1930, Allensworth’s station closed down.

Then, the town suffered the third and biggest blow. In 1914, Colonel Allen Allensworth, the town’s founder, was killed.

It happened near Los Angeles, where he was giving a sermon. He was walking across the street when two white men on a motorcycle ran him over. It was broad daylight on a paved street that was at least 60 feet wide. People who saw Allensworth get hit said there wasn’t any traffic.

Col. Allensworth died from injuries sustained when he was run down by a motorcycle driven by D. S. White. This was a case of Racial hatred and slave catchers who didn’t get their man until it was too late. The col. was a two time runaway slave and on the third time he made contact with the army/ union outfit and became a special assistant to the regiment.

After proving himself he ascended through the ranks and eventually became a lieutenant (light Bird as we used to call them when i was in) so you know the story but they won’t give any details about what happen because certain people don’t like being told about their lack of humanity. Two caucasian males (possibly ex-slave catchers ran him down on a 60 feet wide street right after a sermon he gave at church.

They stalked him for a long time to be able to fine him in California after all that time had passed so hate knows no bounds. There was no police investigation, no body was charged even though it was broad daylight. The law even failed him after serving in the army and serving his country. So they finally got their man.

The fourth and final blow came in 1917. A huge drought hit the Central Valley and lasted off and on for almost two decades.

Allensworth turned into a ghost town.

Most people who live in Allensworth aren’t African American anymore; they are Mexican and Mexican American.

“I guess I grew up thinking I was black because I was raised here,” says Margarita Gonzales, a longtime resident of Allensworth, who goes by Margie.

Margie has lived in Allensworth almost her whole life, but when her family first moved to the town, it didn’t have a water system.

Her family took baths in a nearby canal and drove to Delano – about 13 miles away — to get water to drink.

“We had to go and get water in big, old tanks,” she says.

Eventually, Margie’s family — and the rest of the residents in Allensworth — got tired of hauling water. In the late 1960s, they formed a water company so they could drill a community well. They got financial assistance from the federal government, but the funding only covered the cost of drilling the well.

“I don’t know with the county or whom, they told them, ‘Okay, you guys are the ones that are going to have to make the lines,’” she says.

That meant that the residents, themselves, had to dig trenches for the water pipes that would connect the well to their houses.

There’s no record of why the state or the county didn’t help dig the lines. It was most likely a lack of resources, but it made an impression on Margie.

“They didn’t care, really. It was just a poor black community,” she says.

The well was finished a year later, and Tulare County was put in charge of making sure the water was safe to drink. But it wasn’t safe.

The county tested the well, and that’s when it found arsenic in the water — more than 10 times the legal limit set today.

There are no records that show how long people in Allensworth were drinking contaminated water. It could have been for over a decade.

Stretched Resources

Tulare County was responsible for making sure Allensworth’s water district was doing its job — testing the water and telling residents when there’s too much arsenic.

But the county didn’t do a good job enforcing these rules or helping them find better water.

“It makes me feel that our community is neglected,” says Denise Kadara, one of the residents trying to find better water. “Nothing is happening quickly enough. Why? Why are we still having to do this? Is it because we’re poor? Are we not entitled to safe drinking water, which is a state law?”

In 2014, the state stepped in after it discovered the county was failing to do its job. It found that the county was understaffed and stretched thin.

At the same time, the EPA found that California overall was failing to make sure people had clean drinking water. It basically told the state to get its act together.

The state started helping out a little more. It even sent a water engineer to look at Allensworth’s water system and recommend ways it could improve the town’s water quality.

Ultimately though, it’s up to the water district to find a solution to the arsenic in the water. It’s been trying, but it’s been a very slow, uphill battle.

Like most small districts, Allensworth’s district is in bad shape. When it balanced its books last summer, Sherry told me it had a $13,000 deficit. It struggles with aging infrastructure, a backlog of paperwork, and residents who just don’t pay.

A few years ago, it tried to work with neighboring Alpaugh, which also has high levels of arsenic in its water. But Alpaugh managed to get a water treatment plant from the state because it couldn’t find a place to drill a good well.

Allensworth tried to join Alpaugh’s treatment plant, but Alpaugh didn’t want to work with Allensworth and negotiations between the two communities fell apart.

It seemed like Allensworth couldn’t win. That is, until just last year, when it found a place to drill a well.

But there was another problem.

“We haven’t started construction of the new well because [the California Department of] Fish and Wildlife have a lizard, a leopard lizard that lives out there,” says Sherry.

The blunt-nosed leopard lizard lives on the well site. It’s a fully protected and endangered species which means Allensworth’s water district will need to get a special exemption from the state to even begin the process of applying for a permit to drill on the land where the lizard lives.

“You would think that human consumption is more important than the little leopard lizard,” says Sherry, “but with Fish and Wildlife, that leopard lizard is more important to them!”

To try to get the special exemption, Sherry, Denise, and Dennis, along with Denise’s son and his family, traveled to the state capitol in Sacramento in the summer of 2018.

Sherry and Denise testified in front of the Water, Parks, and Wildlife Committee meeting in an attempt to convince Assembly members to pass a bill that will allow Allensworth to apply for a permit to drill on the land where the lizards live.

Less than two months after the meeting, the bill passed the Senate. Then, less than a month after that, the governor signed it into law.

The Future

The siblings have come close to getting good clean drinking water for their town. But the bill was just one hurdle of many that Allensworth needed to cross.

The town still has to apply for a permit from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Then, it has to apply for more government money to actually drill the well.

It could take another three years of waiting, and there are more obstacles to consider.

Even if Allensworth is able to drill a new well, residents will only be able to drink the water that is close to the surface. That’s because the deeper the well, the more arsenic in the water. The toxin is more concentrated the deeper underground you go.

And it becomes even more concentrated when people pump too much water out of the aquifer.

If you think into the future — when the next big drought hits — it doesn’t require much foresight to guess what will happen. Just look at what the state went through in the last drought: water tables dropped and wells went dry all over the Central Valley.

That scenario is predicted to get worse. With climate change making droughts longer and more frequent, Allensworth may find itself right back where it started.

But the people of Allensworth haven’t given up easily. That’s how Allensworth got its reputation as ‘the town that refuses to die.’

One decade later, however, on May 14, 1976, the California State Parks and Recreation Commission approved plans to develop the Colonel Allensworth Historic Park on the central portion of the town. The process started in 1969 when Cornelius Ed Pope, an African American man draftsman with the Department of Parks and Recreation began a campaign to persuade State Park officials and the general public that the town-site had particular historic and cultural significance for California’s African American population.

Pope related how as a boy he had lived in the house once owned and occupied by the Allensworth family. As a part of the restoration project, several buildings have been restructured to the likeness of the historic period of 1908-1918.In the article above retired California State University, Fresno historian Robert Mikell explores the history of the only all-black town created in the Golden State. He traces that history including the role of its principal founder, Colonel Allen Allensworth, from 1908.

Leave a comment